Special to Feed by Cassie Packard, Eyebeam oral historian

Portrait of Eyebeam Democracy Machine Fellow 2024, Mashinka Firunts Hakopian. Courtesy of the artist.

Portrait of Eyebeam Democracy Machine Fellow 2024, Mashinka Firunts Hakopian. Courtesy of the artist.

Special to Feed by Cassie Packard, Eyebeam oral historian

Mashinka Firunts Hakopian: These projects share a desire to foreground knowledge systems and technologies of knowing that open up otherwise occluded imaginaries. I did my dissertation at University of Pennsylvania on the lecture performance as an artist-activist tool that was used in the 1970s by artists organizing against the War in Vietnam and advocating for more equitable conditions within museums. The strategies they used were similar to those deployed now by activists who are doing the crucial work of calling for a Free Palestine — like the activist pedagogies of the demonstrators who stunningly shuttered MoMA on February 10th by staging a sit-in and distributing informational pamphlets. They were shutting down art spaces and transforming them into spaces of knowledge-making in the service of collective resistance. In one exemplary instance, the artists Faith Ringgold and Tom Lloyd led an unauthorized lecture tour of the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1969, highlighting the histories of colonialism that undergirded the modernist galleries and that led to the formation of Western art history as a corollary of colonial violence and extraction.

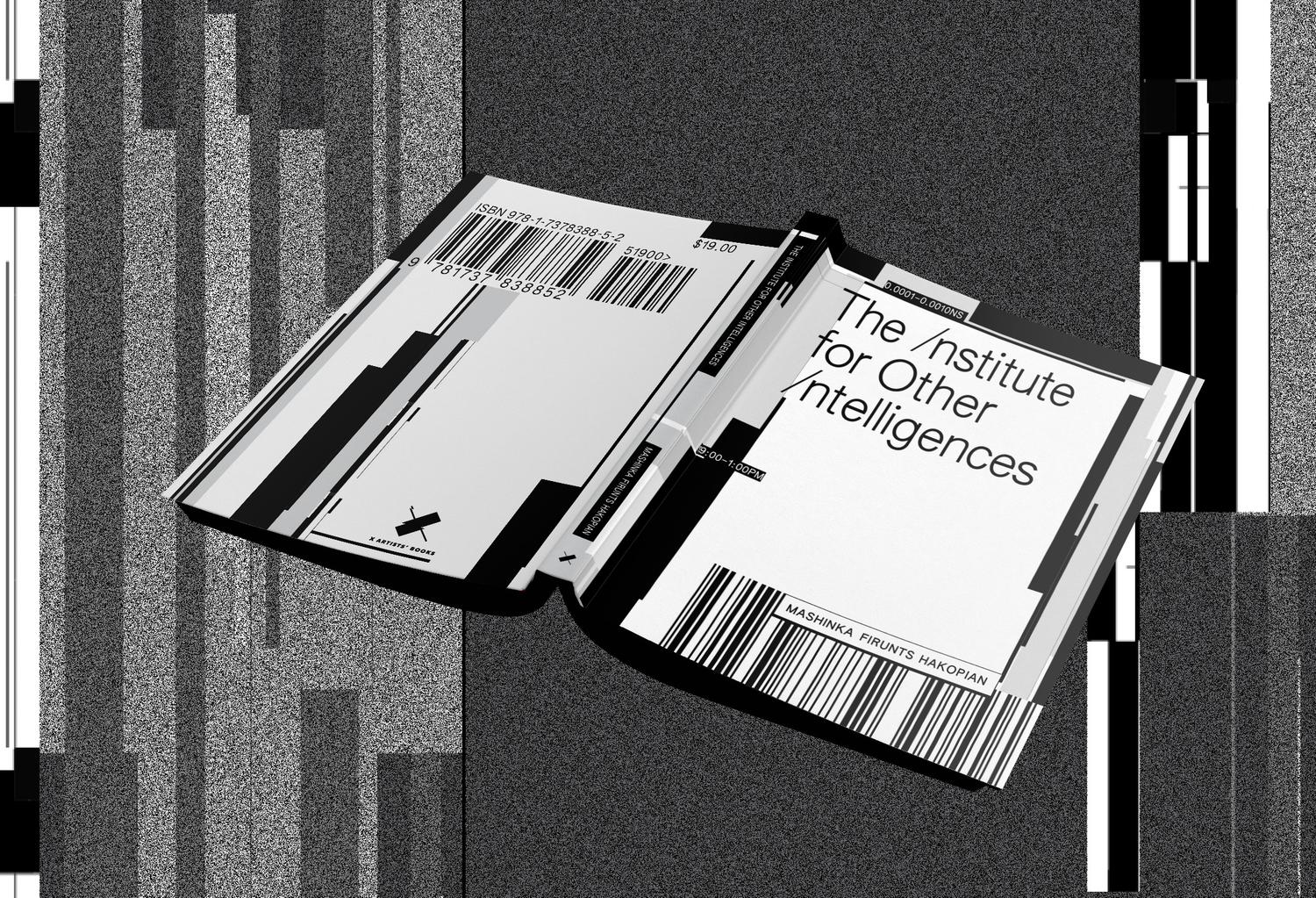

‘The Institute for Other Intelligences’ (Los Angeles: × Artists’ Books, 2022). Edited by Ana Iwataki and Anuradha Vikram. Design by Becca Lofchie Studio. Illustrations by Fernando Diaz. Image by Becca Lofchie Studio.

The writing project you mentioned [The Institute for Other Intelligences (X Artists’ Books/ X Topics Series, 2022)] is a quasi-quasi-scholarly artist’s book. The text draws from critical media studies and contemporary reporting around AI to present a speculative manual for training feminist bots. It was produced in collaboration with a number of people, including Fernando Diaz, a computer scientist who illustrated it with speculative diagrams, designed by Becca Lofchie Studio, and edited by Ana Iwataki and Anuradha Vikram. I later adapted the book into a lecture performance [Dispatches from the Institute for Other Intelligences (2023)], with a musical score by electronic composer Lara Sarkissian, that was presented at the Centre Pompidou and the New Museum. The project offers a data feminist critique of AI as a “view from nowhere,” premised on the question, “How do we deploy what we know if not from within a body?”

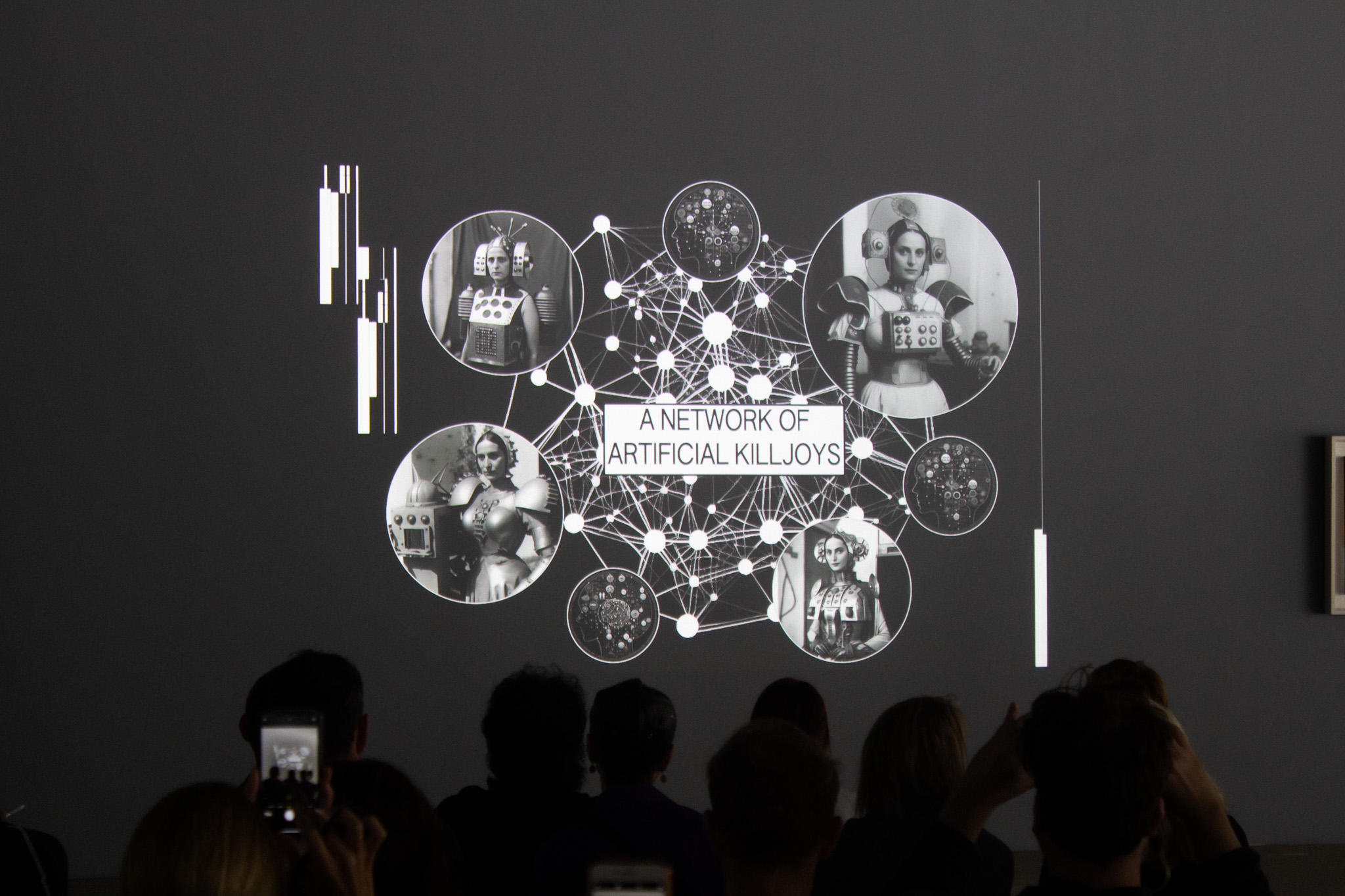

Performance still from “Dispatches from the Institute for Other Intelligences,” Centre Pompidou and Kadist, “The Future Isn’t What It Used to Be” Symposium, July 13, 2023. Photograph by Justin Musyimi.

My lecture performance practice, which originated in collaboration with Avi Alpert and Danny Snelson as part of the collective Research Service, grew out of reflecting on—and wanting to intervene in—the presumed neutrality of the lecture as a technology. This practice focuses on embodied and practice-based forms of research, particularly those that emerge in community contexts. The project I’m doing as part of my Eyebeam Fellowship is working within that model, as well.

Kamee Abrahamian, Nancy Baker Cahill, Mashinka Firunts Hakopian, and Nelli Sargsyan, ‘Monument to the Autonomous Republic of Artsakh,’ 2020. Augmented reality monument geo-located on Artsakh Avenue in Glendale, CA. Viewable through the 4th Wall app.

Hakopian: The project fits within a larger body of work exploring ancestral intelligence. I approach ancestral intelligence as ways of knowing that are embodied, transgenerationally transmitted, and often drawn from SWANA cultural histories—ways of knowing that are underrepresented, undervalued, and typically confined to obsolescence within dominant AI discourses. In the rhetoric of hyper-novelty that I see around emerging technologies, we are always implicitly being asked to accept what came before as obsolescent. And “what came before” is tacitly understood as non-Western, Indigenous, or otherwise underrepresented ways of knowing. Ancestral intelligence intervenes in that formation, refuses hyper-novelty, and insists on an expanded view of technology. What happens, for example, when we recognize tasseography (coffee ground reading) as a predictive technology?

In the context of One Who Looks at the Cup, I’m thinking about what it means to model AI that predicts multilingual, collectively authored futures that are rooted in ancestral pasts. This multidisciplinary artwork and community data project centers practices of prediction that come from SWANA coffee ground readings, a divination method used for hundreds of years that predicts the future by detecting visual patterns in coffee grounds. As the sociologist Carina Karapetian Giorgi writes, this is an intimate form of knowledge exchange that takes place in domestic environments rather than institutional settings. Giorgi also writes that this form of divination was matrilineally transmitted as a means to imagine survival within Armenian diasporic communities after the Armenian Genocide in 1915.

More broadly, tasseography privileges intuitive knowledge: what you believe you see in the future when you look at the cup, over and against any kind of Western scientific positivism. In the present, it helps us think about forms of intuitive knowledge that we might value and embed in emerging technologies, over and against scientific algorithm prediction.

Hakopian: The research process will center on community dataset creation. The data used to train the model will be assembled through coffee ground readings that I conduct with SWANA members of my communities. The readings will be audio recorded; the image of the coffee grounds at the bottom of the cup will also be captured. That training data will be transcribed and translated from English to Armenian, or from Armenian to English, and used to code multilingual outputs. The readings will involve conversations on the topic of liberatory futures, so that when this model begins producing outputs, the futures that it’s divining emerge from perspectives and lived experiences that are structurally omitted from dominant models of futurity. I put a fine point on this because we’re living through a moment when so many forms of SWANA futurity are being violently foreclosed: a moment that, over and above and beyond any aesthetic response, demands coalitional organizing and collective action.

Hakopian: Yes, in multiple ways actually. My research focuses on art and technology, as well as on diaspora studies. I moved from Yerevan to a densely Armenian immigrant community in Glendale, California — unceded Tongva land — as a child. My grandmother lived here for about 16 years and elected never to learn a word of English beyond the word “no,” which she only learned so that she could communicate to English-speakers that she was declining the language. I’ve previously done work with a tenants’ rights group, the Glendale Tenants Union, thinking about what it means for a diasporic community to arrive in Glendale after being repeatedly displaced and dispossessed and then find themselves, through structures of economic injustice, being displaced again. That economic violence has also been coupled with acts of cultural erasure, for example during the so-called “Glendale Biennial” in 2018. We’re seeing the intensification now of precipitously rising rents and the lack of tenant protections in this city, and beyond. Some of the work I do focuses on language justice and interpretation, informed by the work of Antena Aire and language justice advocates like Jen/Eleana Hofer and Hayk Makhmuryan. In the housing justice context, that work supports access to participation in tenants’ associations, city council meanings, etc. in one’s own language.

From a coffee reading with the artist conducted by Ani Carla Kalafian, 2023.

Hakopian: In the ideally realized version of this project, it will be able to produce multilingual outputs across several languages including Armenian, Farsi, and Arabic. For resourcing reasons, for now, its outputs are going to be bilingual (Armenian and English). Considering the role of language in relation to AI is crucial because language, as we know, is a technology for encoding knowledge. I’ve been thinking about this through the concept of algolinguicism, which is a matrix of automated processes that minoritizes speakers of non-dominant languages and obstructs their access to political participation. The essay you mentioned, which I wrote a couple of years ago for the AI Now Institute series, “A New AI Lexicon,” looked specifically at the case study of Azerbaijan, which is notoriously involved in a sprawling campaign of state-sponsored digital repression that results in the silencing of dissident voices, with real political and material outcomes. One reason this campaign has been allowed to flourish in digital spaces like Facebook and Twitter is that content moderation algorithms are only coded to work in certain languages that digital platforms consider “priority languages.” Looking at case studies like this one—and this is only one of manifold instances of algorithmic harm caused by the marginalization of non-dominant languages—begs the question of whose languages and whose knowledge systems encode possible futures. And that’s one of the questions that One Who Looks at the Cup is asking.