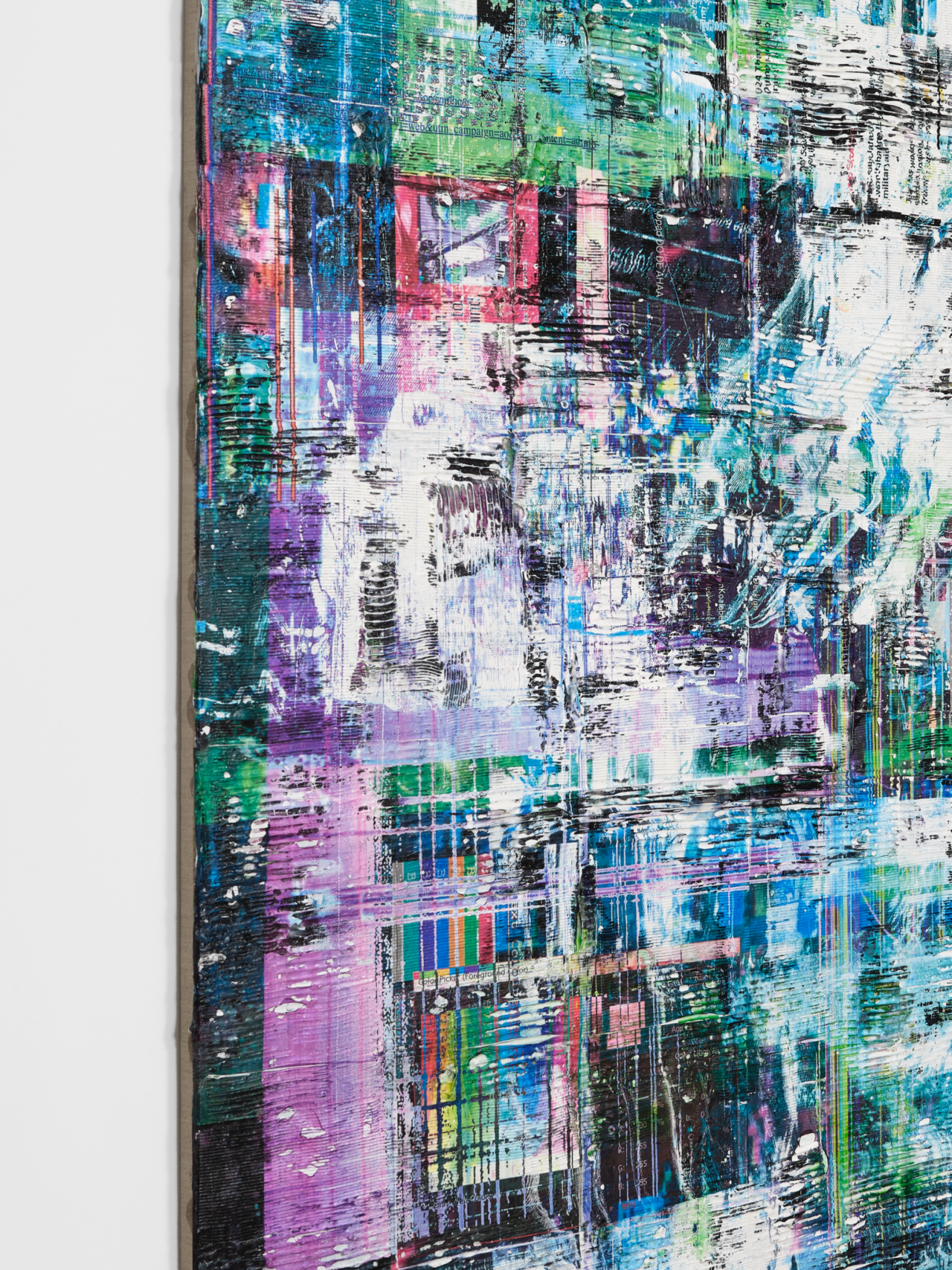

Dorland’s recent bodies of work about the space of the computer screen still exercise technical prowess to reflect on machine-made images. But in these paintings the screen doesn’t look glitched so much as utterly destroyed, collapsed under the weight of its many iterations over time. The riffled striations that characterize these paintings both evoke the movement of light through an LED screen and the streaking of ink in a jammed printer; their textures shimmer between material and effect. The content of his paintings comes from screenshots of his desktop, arrangements of icons and code in action, layered digitally and then physically in a play of inputs and outputs. In several works, a film of UV coating laid over the surface bunches and ripples like skin. Dorland’s working over of the surface makes the immaterial recesses of digital space feel visceral.

Dorland and Woolbright both overlay moments in one overall image, compressing the screen’s varied appearance on a single plane, where hazes and goos express both time stretching out and the mess of apprehending it all at once. Schoolwerth, too, foreshortens the temporal experience of digital media. His “Rigged” series (2022) assembles 3D models purchased in marketplaces largely used by fan artists, video game designers, and architecture interns charged with populating mockups; these are paintings about online impulse shopping. The scenarios deicted in the works vaguely recall classical academic painting, but are too twisted to line up with any known myth. The Architect of Wheelbarrow Park (Rigged #22), 2022, loosely outlines a scene of seduction, but it takes place in a suburban yard. The seducer has a translucent torso and a pink brushstroke for an arm; the prey languishes in a wheelbarrow, one limb careering upward and growing into a grinning Kim Kardashian. Their love triangle is complicated by other ghosts and shadows who haunt the space between house and fence, triangulating the mythic, the supernatural, and the banal. Encountering this overstuffed tableau, the gaze gets split into multiple directions at once, struggling to make it all cohere.

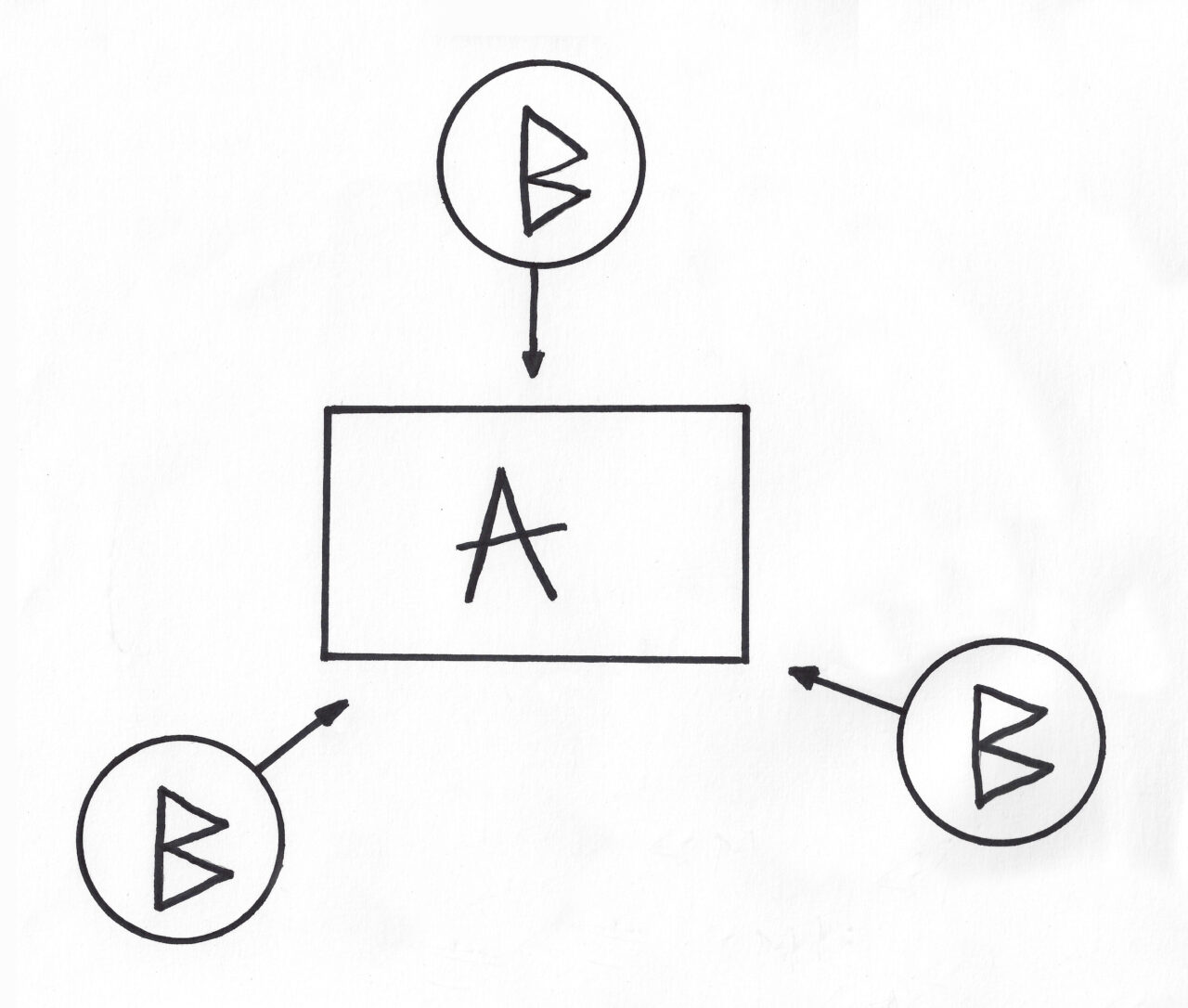

Each figure in “Rigged” comes with its own aura, the trappings of the genre it was designed for, be that an airline ad or a horror game. Schoolwerth picks up models made at different times—2003, 2010, 2018—and each is marked by the textures and levels of definition available to its creator. They’re also modular. The title of this body of work refers to the “rigging,” the 3D model’s skeletal figure that bears its surface textures. When put together as intended, the hair texture goes on the head and clothing textures clad the body. But Schoolwerth sometimes shifts the surfaces across the rigging, or puts the skin of one model on another’s skeleton, to achieve smearing, warping effects.

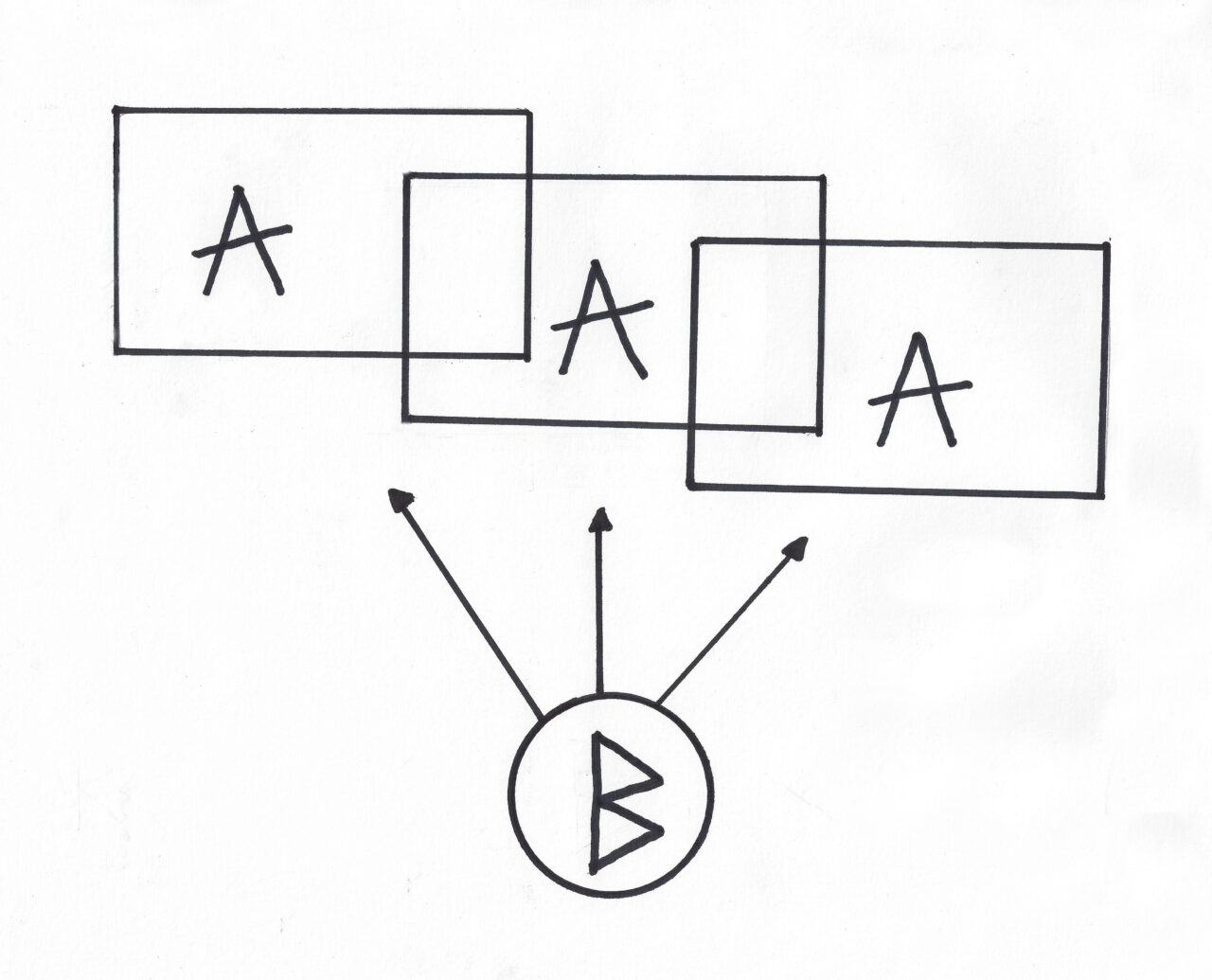

Schoolwerth has always been fascinated with Baroque maximalism, and he seems to delight in the mistakes of its mediocre examples, where figures compiled from sketches and etudes don’t quite fit, their gazes and gestures misdirected if they don’t quite occupy the same space. Schoolwerth has addressed the history of academic painting in various ways over the years, breaking it down to component parts. His 2010 series “Portraits of Paintings” compiled tracings of figures from classical painting as models of the fragmented contemporary subject. In “Model as Painting” (2017), he revisited the practice of making shadowbox models by carving compositions in foamcore, then scanning them in Photoshop, to create absences and layers in software that were informed by their physical residue. In “Rigged,” Schoolwerth treats classical compositions as a kind of rigging, and the figures in them as the skin. Just as he does with the models themselves, he warps and warps these rigs to achieve effects of excess and disarray. Whereas Woolbright creates new structures of underpainting and populates them using painterly techniques, Schoolwerth adapts the rigging of classical painting to digital media and uses the capabilities of software to stretch it and remake it; Dorland experiments with both structure and technique, seeing what happens to the format of painting when its tools are integrated with—or swapped out for—the computer’s peripherals and the iterative processes of software.

***

I’ve been fortunate to have access to the studios and time of Schoolwerth, Dorland, and Woolbright in recent months, and that’s why they’re the artists I write about here. But there are others whose work stages dialogues between the foundations of painting and the possibilities of digital media. Caitlin Cherry re-creates thirst traps found online with wild palettes and goopy textures. Her paintings look great when the images return transformed to Instagram, but reward in-person study, too, with the richness of color and compositions that foreground the conventions of painterly portraiture that persist in social photography. Austin Lee’s early work reverse-engineered the look of painting programs for the iPad, using spray cans to simulate the hazy halo of the simulated brush. He still dips into the feedback loop of paint, the digital rendering of paint, and the physical rendering of digital paint. Avery Singer uses a robotic apparatus to apply paint to canvases, realizing software-made compositions that splice the conventions of constructing space in digital and painterly environments.