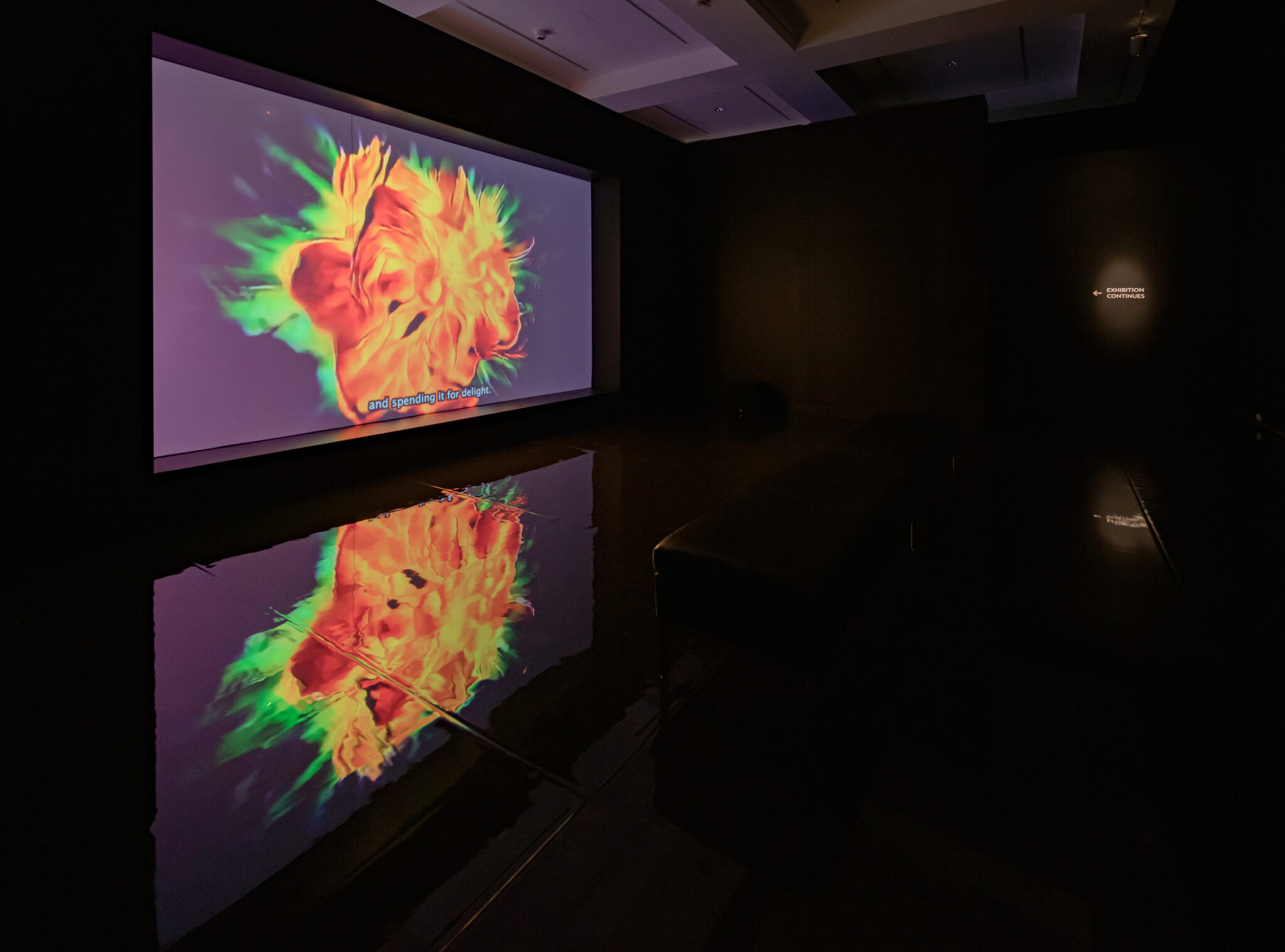

This is the Future (2019), a filmic essay by Berlin-based artist Hito Steyerl, is about the eternal and eternally useless human quest to predict what lies ahead. In woozy, continuously melting footage, we glimpse Stonehenge as an ancient divination tool before traveling to the immediate future. Our protagonist is Heja, a woman imprisoned for a yet-uncommitted crime predicted by a neural network. As a narrator, the neural network explains how it based that prediction—as well as that of credit rates and life spans—on “extreme probability.” Suddenly an alarm sounds.

“Danger! The future poses a 100% risk for human health,” the network warns. “Statistically, in the future, all humans will die.”

In Steyerl’s satirical rendering, artificial intelligence is a bumbling, glitching idiot, crunching pretty unassailable logic into absurdly sensational conclusions. This is more or less an accurate portrayal of how the technology works. AI “generates responses based on patterns,” ChatGPT recently explained to me; programs like the popular chatbot take vast quantities of data and boil them down to a series of averages and probabilities, scrubbed of extremes and outliers. These datasets are then used to make predictions: a conversation with ChatGPT is simply a string of statistical likelihoods derived from language models, just like certain softwares will identify potential criminals based on who’s already in prison. To Steyerl, AI amounts to a plodding brute force that blunts the messy complications of reality into a series of neat statistics and dehumanizing algorithms—no nuance, no compassion, and no common sense. Rejecting “artificial intelligence” as a misnomer, she prefers the term “artificial stupidity.”